Despite their name, sea cucumbers are not fruits, vegetables or any sort of plant. They’re animals—ancient, slow-moving, wonderfully strange animals that have been cleaning and recycling the ocean floor for millions of years.

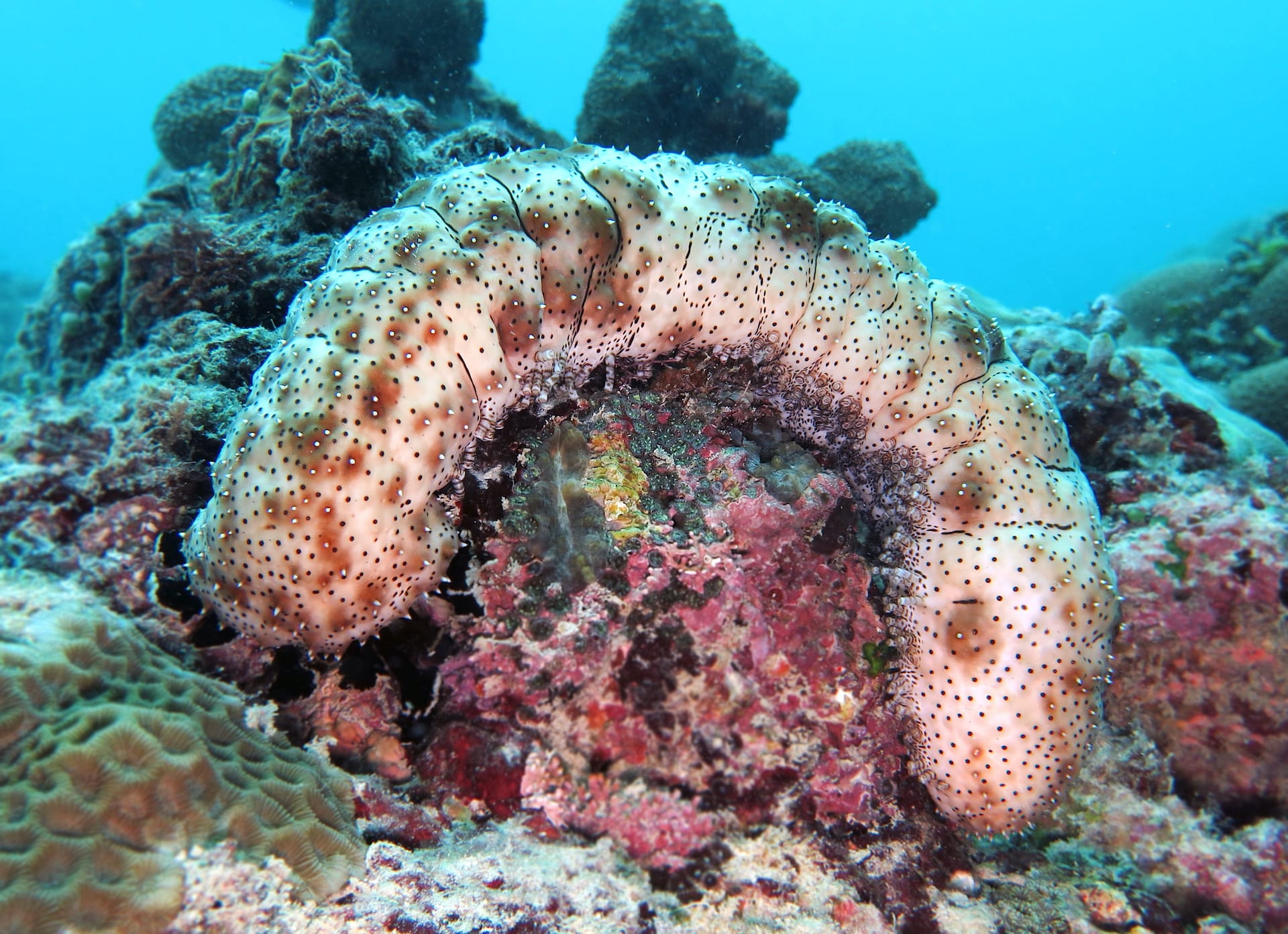

Sea cucumbers belong to the class Holothuroidea and are close relatives of sea stars and sea urchins. More than 1,700 species are found worldwide, living on the seafloor from shallow coral reefs to the inky darkness of the deep sea. Many have soft, water-filled bodies and leathery skin, giving them their cucumber-like appearance, but don’t be fooled—this group comes in an extraordinary range of shapes, sizes and colours. Some are only millimetres long while others can reach a whopping three metres.

Like all echinoderms, sea cucumbers have five-part body symmetry, a mouth at one end and an anus at the other. Instead of a hard skeleton, they rely on tiny particles of calcium carbonate called ossicles, which act like microscopic armour. This flexible structure is the reason behind their “squishy” look and feel.

Nature’s Recyclers

Sea cucumbers play a vital ecological role on the Great Barrier Reef. Most are scavengers, sucking up sediment packed with organic material. They digest the nutritious bits—algae, plankton and detritus—and then expel the cleaned sediment behind them. This constant churning of the seafloor is known as bioturbation, and it helps to:

· recycle nutrients

· oxygenate the sediment

· produce calcium carbonate used by corals and other reef builders

In short, sea cucumbers help keep the Reef healthy from the bottom up.

Stranger Than Fiction: Fun Facts

Sea cucumbers boast some of the most unusual adaptations in the animal kingdom:

· Self-evisceration: When threatened, some species literally eject their internal organs through their anus to distract predators. They later grow them back.

· Sticky defence threads: Others fire out long, sticky strands to snare would-be attackers.

· "Butt breathing": Without lungs, they pump water in and out of their anus to extract oxygen using specialised respiratory trees.

· No eyes, no heart, no brain: Yet they navigate the world using a nerve ring and sensory cells in their skin.

Life and Threats on the Reef

Most sea cucumbers reproduce by releasing eggs and sperm into the water column, letting the currents do the mixing. In cooler regions, some species keep their fertilised eggs inside the body until the young are ready to swim free.

Despite their tough survival strategies, sea cucumbers are preyed upon by fish, crabs and turtles. They also hold significant cultural and culinary value throughout the Indo-Pacific. Known as trepang, bêche-de-mer, namako or balate, they are harvested for food and increasingly farmed in aquaculture systems.

However, many species—including several found on the Great Barrier Reef—are under pressure. Overfishing, both local and global, has driven some populations to dangerously low numbers. Troublingly, several heavily fished species show little sign of recovery, even years after harvesting has ceased.

The Unsung Heroes of the Seafloor

They may not be glamorous, fast or fierce, but sea cucumbers are indispensable to the health of coral reef ecosystems. By cleaning, recycling and reshaping the seafloor, they quietly keep the Great Barrier Reef functioning.

Perhaps it’s time we stop overlooking these humble creatures—and start appreciating them for the remarkable animals they truly are.

Sea Cucumber. Photo supplied.